The video of the 250th anniversary service (delayed three years for the pandemic) of Murray’s landing in America, held at Universalist National Memorial Church on October 7, 2023 may be seen here. (Facebook)

Remembering Universalist Heritage at Jubilee celebration

The Universalist National Memorial Church held a convocation on October 7, 2023 entitled “Universalist Jubilee: Its Legacy and Promise.”

The video will become available at some point and I will link it here, but in the meantime these are the notes from my part of the service.

Friends, where have we as Universalist come from? A few words. Look to the window to my right. It depicts, or is intended to depict, the Hand-In-Hand, the vessel which brought John Murray from England to America on September 30, 1770. This is the anniversary we remember today: the point from which we mark the 250th anniversary of Universalism in America. By the time he landed at Barnegat Bay, New Jersey, he was already a broken man. His change of faith within British evangelicalism lost him most of his friends and probably successful career. Then his wife Eliza and their son died. He landed in debtors’ prison, and once out we wanted to lose himself in the world, particularly the great American wilderness. That’s why he came here. But even the ship, bound for New York, was off course. The grace — almost miraculous grace — of his encounter with Thomas Potter encouraged him back to the ministry, and back to life. It’s a well-known, oft-told story, too long to repeat now, but it’s a story we need to tell more often. Murray did not plant Universalism here. There existed groups and individuals up and down the Eastern Seaboard who felt, thought and believed as he did: believing in a perfect hope of God’s complete salvation. One such group was the nucleus of what would be the first Universalist church in America, in Gloucester, Massachusetts. And one of those he met was Judith Sargent Stevens, a writer in her own right and today more famous than this minister she would later marry. The irony was that his own theological and homiletic approach to Universalism, the would-be denomination he supported and his lineage of leadership within the fellowship of churches faded in his own lifetime and he was quickly overtaken by others whose names are also a part of our heritage. But Father Murray was as much a model of Christian life and a preacher or pastor. He suffered disappointment, depression and loss. We can understand him, and trust that he would understand us. His faith that God saves, and saves completely returns us to hope. Little wonder this church’s first iteration was a memorial to him. While the vision in and from Universalism was grand, our numbers never were. Numerically, we have been been in decline for generations. In 250 years, will there be Universalists who look through us, to Murray’s landing in New Jersey? The question is not important. Rather, as with others before me, I trust God and trust in God. I trust God will be true to the divine nature, a nature that we profess as love. Not that God is loving, but that God is love itself. And that love will not betray or fail us. Our existence is not a failure in the universe. New people rediscover and reconstruct this faith all the time; it will not die. So I trust in God, that there will always be a witness for the larger faith, whether in our fellowship or another. Occasions change and plans fail, but the providing grace of God endures. Those who will listen will hear the truth. So at this anniversary celebration, we can look back to Murray’s landing and return to life. Behind him we see the Reformation, and the Apostolic church, and back to Calvary where this world was redeemed, and from that to the foundations of the world. There, with the Creator, “whose nature is Love” we find our legacy and our hope.

Why deacons and baptism?

My interest in deacons and baptism in Universalist churches isn’t arbitrary, and it’s not about the past. It’s about the future.

I figure the remaining Universalist Christians within the UUA are going to have to rely on each other and the ecumenical church more in the future, or perish. Those “new Universalists” who gather into distinct churches might want to know what makes “denominational Universalism” cohesive and distinct. So, where do we stand? Where have we stood? Do you have a good answer to that? I don’t.

What I think Universalists had was a churchly culture to rely on when there were gaps, and a culture of tolerance (or indifference) where there were conflicts. We no longer have the one, and the other leaves you gasping when you ask, “what do you believe in?” (I don’t think Unitarian Universalists of any stripe deal with this in a convincing way, and this might contribute to its self-isolation and sectarianism.) I’m finding bits and pieces that glint in a fast moving, occasionally murky, stream.

I felt a sense of historical and theological isolation keenly when I was in seminary, in a class which studied the landmark 1982 document Baptism, Eucharist and Ministry. We students were expected to bring our denominational response to it to class and reflect on it. The Baptist students and I commiserated — and scrambled for a make-do. I ended up using the response (Archive.org) of the Remonstrant Brotherhood (site in Dutch), which was the closest “relative” that made one.

I’m not suggesting future Universalists are bound to decisions past Universalists made on these matters, especially if they were made poorly, grudgingly or in couched terms. Perspectives on one ordinance (the Lord’s Supper or Eucharist) and one of two orders of ministry (pastor) are better understood. Focusing on the other ordinance and other order of ministry might inform me and my readers about how past Universalists saw themselves. And from that method, we might be able to reconstruct an authentic Universalist voice, and then assess it has what we need in the future.

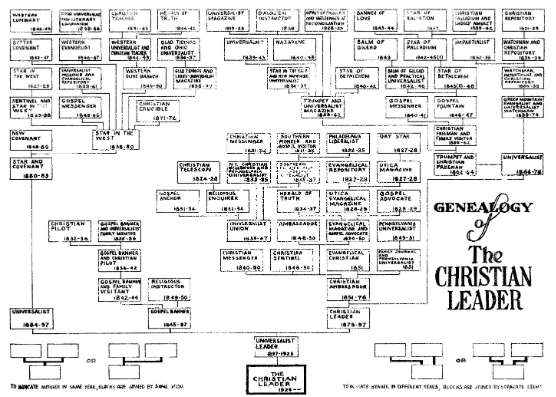

Universalist newspaper family tree

Universalists loved their newspapers. They spread Universalist doctrine and culture, particularly in areas where there there were no churches or no resident ministers. Controversies played out in them, news propagated through their pages and late into the pre-consolidation era, the polity required notices be published in them. Last week, I found more than a decade of pre- and post-consolidation Universalist magazines, which are the antecedent of today’s UUWorld, and the heir of dozens of Universalist titles. Universalist loved their periodicals, but not always liked paying for them and so the history is made up of consolidation upon consolidation.

I was looking for, and today found, this chart (linking from this list of publications at the Harvard Divinity School Library site) which I had seen before but lost the citation. It charts out the antecedents of the Christian Leader, which would be renamed on more time to the Universalist Leader before being merged with the Unitarian Register. Which means that these aren’t all of the Universalist periodicals that existed. Some winked out of existence before it could be merged with another. And then there’s the Universalist Herald, which survives and never merged, still going since 1847. (Go ahead and subscribe.)

Sermon: “John Murray in 2020”

I preached from this sermon manuscript online for the Universalist National Memorial Church, on September 27, 2020 using lessons from the Revised Common Lectionary: Ezekiel 18:1-4, 25-32 and Matthew 21:28b-32. [shortened lesson]

Wednesday marks the 250th anniversary of John Murray’s arrival in America. Later dubbed the “father of American Universalism” and considered for generations its signal pioneer, in a person, John Murray stands for Universalism. The stained-glass window of the ship in our church building (second from the front, pulpit-side) represents the ship that brought Murray to America, so represents Universalism in the life of the Christian church. Our church’s original name was the Murray Universalist Society, and for a long time the church was planned to be a memorial to him personally. So, today’s anniversary celebrates him, the Universalist church, where it has been and where we are going.

You may have seen the lithograph of Murray in the vestibule at church. Not the big one in the rectangular frame of a man presiding over the Lord’s Supper. That’s Hosea Ballou, important in his own right, but he belongs to the generation after Murray and in many ways replaced Murray’s theology. But rather the profile of a man in an oval frame just before you go down the hallway to the parlor. It’s a bit faded, rather small and easy to miss — just like our understanding of Murray, and even the world’s understanding of Universalism and what it points to: the empowered nature of God, which will save all.

There’s a contradiction between John Murray as an emblem, and the common knowledge about him. Why is that?

The story so far

Since we will be joining First Universalist, Minneapolis next week in their service as part of Murray Grove‘s observance of the anniversary, I won’t preach this sermon the way I normally would. There are usual and customary ways to talk about John Murray, his arrival, and ministry — Murray Grove, Thomas Potter, “this argument is solid, and weighty, but it is neither rational nor convincing” — so there’s a good chance we’ll hear all about it next week, and if not then, than eventually.

Suffice it today that Murray did not come to America to evangelize, but at age twenty-eight was already a broken man. The ship he was on was bound for Philadelphia, but arrived off the central coast of New Jersey and got stuck on a sandbar. He was part of the landing party to get supplies — so no auspicious disembarkation — when he met an elderly man, radical in his beliefs, who was convinced that Murray was the preacher of universal salvation that God had long promised. He even had a meeting house ready for him to preach in. Was it providence? A tale later reshaped to sound better? Simple luck? Whatever the case, later generations of Universalists made this the origin story and bought the site as a retreat; it still exists, you can visit, and the center — Murray Grove — will be our hosts next week.

Celebration

But first things first: let’s celebrate this. We have come far in faith. We’re not big but we have survived with our integrity, our community and our legacy intact. He have a heritage that has depths to inspire us and encourage us. It’s like being the father of the prodigal son, who thought that his son had died. We have something to celebrate, so let’s not take that for granted. I could use a little celebrating about now.

And further by looking at this heritage, and though the lens of today’s lessons, we have notes that lead us to a better and more generous spiritual life, and a closeness to God that gives us strength in times of need (and why we gather as a church.) We have much to celebrate.

The anniversary

Of course, we are not the first to mark the day. 150 years ago there was a centennial convention in Gloucester, Massachusetts that attracted twelve thousand participants, the largest meeting either the Unitarians or Universalists ever held. Even fifty years ago George Huntston Williams wrote an essay, American Universalism, which is still a standard source for interpreting the history, and is still in print. (I recommend it.)

But what is it 250 years ago that we are marking, apart from a trans-Atlantic passage? What’s the meaning of the story? I think it’s the failure of misplaced intent and a redirection towards new life. In other words, life doesn’t go according to plan and those changes can have their own consolations. Murray’s voyage, or at least the way we usually interpret it, is itself theological.

A bit more context. John Murray was born in Hampshire, England in 1741 but brought up in Ireland, by his father, a merchant. He was a Calvinist within the Church of England; severe and smothering, today we would consider the elder Murray as emotionally abusive. John understandably, if selfishly, left his family when his father died, as a part of the famous evangelist George Whitefield’s entourage, later settling in London and attending Whitefield’s Tabernacle. That’s when he met and later married Eliza Neale. (Her family did not like him.)

Nearby, a former disciple of Whitefield named James Relly was stirring up trouble by teaching that Christ took on human nature completely, and so in his saving acts, saved the human race completely. And the infection was beginning to spread.

So Murray was sent to correct one of these poor deluded Rellyites — and you can see this coming, right? — she got him thinking that Relly might be right: that all human beings were saved, not maybe or optionally, but as a condition of salvation itself.

But he and Eliza became convinced of Relly’s teaching and joined his Universalist church. In falling away, they lost their friends.

Murray in London

He and Eliza might have had a happy life together, even if without material riches, and going down in the annals of English Dissent as a later rival to John Wesley. But their son died in his first year, and then Eliza’s health declined. In a dreadful story familiar to people today, John did his best to care for his sick wife. They moved four miles out of town, to a healthier environment, even though that meant he had to walk eight miles each day to earn a living. He spent all he had on doctors, nurses and medications. But nothing worked, and Eliza died too. Widowed and destitute, John ended up in a private prison for debt. If his brother-in-law hadn’t paid his debt and and given him a job he might still be there.

He was despondent. It seems he contemplated suicide, but considered a sin and chose instead to “to pass through life, unheard, unseen, unknown to all” in the wilderness of America. That’s how he ended up on that ship, landing 250 years ago.

What a strange thing to celebrate.

Why Murray?

So maybe you’re wondering, why does John Murray get the pride of place? He wasn’t the first person to preach universalism and either Britain or America. There were already Universalists that met him on every important stage of the journey, some of whom had very different ideas of how God would save humanity. One reason surely is that he was the pastor of the first explicitly Universalist church in America, but even it rose out of group that studied the works of James Relly. He later became the minister of the first Universalist church in Boston. And he had a reputation of being a popular preacher. But there were other popular preachers, and (surprisingly) his particular theology barely survived his own lifetime.

Maybe it’s because he was a careful and intelligent writer, but that’s not really the case either. He didn’t leave a systematic theology or textbook, or a series of arguments like other more influential theologians.

Even though three volumes of his letters and sermons exist, they were very hard to come by until the mass scanning of books a few years ago, and I was many years into the ministry before I actually saw a copy! That’s because they weren’t reprinted and kept alive by later generations, because, to put it nicely, they don’t age well.

In the 1780s, Murray had some legal problem about the Universalist church being a separate entity, and so weddings he officiated that might or might not have been legal. He went back to England until the matter was settled. He returned on the same ship as Abigail Adams, and so we have her impressions of her in her journal:

Mr. Murry preachd us a Sermon. The Sailors made them-selves clean and were admitted into the Cabbin, attended with great decency to His discourse from these words, “Thou shalt not take the Name of the Lord thy God in vain, for the Lord will not hold him Guiltless that taketh His Name in vain.” He preachd without Notes and in the same Stile which all the Clergymen I ever heard make use of who practice this method, a sort of familiar talking without any kind of dignity yet perhaps better calculated to do good to such an audience, than a more polishd or elegant Stile, but in general I cannot approve of this method. I like to hear a discourse that would read well.

Snobbery aside, we can say that John Murray was not a polished writer. But there was someone who did write in an elegant formal style. In that book study group that became the first Universalist church was a wealthy young widow, Judith Sargent.

In time, John and Judith married, and if you happen to study eighteenth-century American history, you are more likely to know about her than him, in part because she was a published author, and particularly because of her her early 1790 essay On the Equality of the Sexes.

If you visit Gloucester today, the mural on the wall is of her. The research institute is about her, not him. The famous portrait (by John Singleton Copley no less) is of her, not him. And we know more about her inner life, through the preservation of her works and private correspondence, than his. A museum exhibit currently running is about her. And if John didn’t write a training manual, Judith did, in the form of a catechism.

If you visit Gloucester today, the mural on the wall is of her. The research institute is about her, not him. The famous portrait (by John Singleton Copley no less) is of her, not him. And we know more about her inner life, through the preservation of her works and private correspondence, than his. A museum exhibit currently running is about her. And if John didn’t write a training manual, Judith did, in the form of a catechism.

The critical John Murray

By contrast, John Murray is little known and little read, even in our church circles. There is no critical edition of his works, and apart from shabby print-on-demand copes, you can only find them in libraries or on-line.

Even the bit of Murray quoted in the gray hymnal (704) is not only not from Murray, but comes from a modern inscription, addressed as if to Murray.

But if I had to bring back one work, and to answer the question, “why John Murray?”, it would be his autobiography, the Life of Murray and Universalists read inspirationally for generations. (Judith wrote the last section.) It was kept in print though the nineteenth century, and I have a copy given “from Minnie to Vesta” as a Christmas gift in 1899. I think because it had a reputation of being inspiring rather that deep, but from that must have come affection and recognition; the book is also how we know his story. Here was a man who knew early abuse, the temptations of friends and the allure of the city, grievous loss, imprisonment, a quest, the grace of God and a new chance. And all he wanted from it was the chance to tell you that God is love, and that all of us are included in God’s salvation. That’s why I think Universalists really cared about him.

Theology

Now, as I said before, John Murray barely outlived his own theological contribution to Universalism, but what was it he believed? It was easier for later generations to honor the man rather than his beliefs, so they weren’t widely discussed. Precisely because his beliefs were controversial, he preferred to preach around them early in his career, leading hearers to come to the conclusion that all persons would be saved, rather than just saying it outright. We can use some of writings near Murray to get a reasonable reflection of what he believed.

What we do have at hand was the book James Relly wrote, Union; a late profession of faith by a church in Connecticut that was the last reference to a living example of Murray’s theology and later secondary writing.

A distinctive feature of Relly-Murray theology is role of Jesus Christ as the captain of humanity. They believed that that God became human in the person of Jesus Christ, meaning that God not only had a knowledge and participation in our human nature, but that as the Second Adam, Christ put on humanity — us, collectively — as you or I might put on a garment.

Thus it was not Jesus alone who died on the cross, descended to hell, rose from the dead and ascended to heaven; rather, we all did. It is now a part of our human nature. To be human is to be saved.

Then what is the purpose of the Jesus’ teaching or the role of the church? In a sense, it is to unlearn what we have come to believe, and be bound by it. Most people don’t believe to be human is to be saved, so they (or we) must be saved from our unbelief in the goodness of God. Those who do not believe such will suffer a kind of living hell feeling, but not actually being, alienated from God. Thus we do no earn salvation, but know int. This gives the Universalist church its purpose: to spread the good news of what has already and what must forever be.

Rivals to Murray included Elhanan Winchester in Philadelphia, and his belief that God will fill all promises and salvation shall one day surely occur. (He and Murray did not get along.) Also, Hosea Ballou who made a common-sense argument from the nature of divine justice, that finite beings are not liable for infinite penalty, and this was already taking over in Murray’s final years.

A word or two about our lessons.

Ezekiel

Ezekiel was one of the prophets, and probably one of the hardest to appreciate and understand. Culturally, he’s known from the gospel song, “Ezekiel Saw the Wheel,” a reference to a manifestation of heavenly beings. These heavenly beings — an amalgam of eyes and wheels and wings — that on the one hand is a stunning metaphor for the omnipresence and omniscience of God. But on the other hand have encouraged lurid and literal images of what they would look like. Real nightmare juice. Ezekiel is fodder for 1970s conspiratorial pulp paperbacks to suggest that Ezekiel actually met beings from other worlds, the “wheels” being their spacecraft.

He’s hard to understand because of the intensity of his visions. For Murray, that meant Ezekiel pointed a straight line to universal salvation, but from another part of the book. (Surprise, surprise.)

And yet Ezekiel is not so strange as to be ignored; at the church, in the chancel rail there are carvings of the four living creature within wheels, emblems which are also use to depict the writers of the four gospels. So think of Ezekiel like a live electrical wire: hazardous, but helpful with approached carefully and with understanding.

In our passage, God tells the prophet to end an ancient saying: “The parents have eaten sour grapes, and the children’s teeth are set on edge.” What does that mean? That we each bear the guilt for our own actions. What this doesn’t mean is that each of us are liberated from the actions of those who go before us. People, much too often, do not get what they deserve because the conditions they’re born into. This passage tells us that children (for example) to do deserve to be born into war, into hunger, into being poisoned or threatened by their environment. They do not deserve this, and yet too many get it. Human justice (or injustice) is not God’s, and we ought to remember that even if we carry a grudge or anger, that this doesn’t compel God to share it. Rather, we should try to see situation from God’s point of view, or at least another point of view before deciding what is right or wrong.

Matthew

In the passage from Matthew, Jesus speaks of the way of righteousness.

The John in the lesson from the Gospel of Matthew was not John Murray, of course, but John the Baptist, who had been teaching and stirring up controversy. Jesus was having a dispute with learned teacher, and made the point that those who do the right thing do the will of God, rather than those who say the right thing. Or put another way, without the correct, corresponding action, pledges and promises are meaningless or worse.

The same is true of beliefs. You can agree with an idea, but if you don’t understand it, what do you really believe? Or you can agree with an idea, and profess it, and really understand it, but act like it’s not important, what then do you really believe?. In other words, you can be a hypocrite, but you’re not fooling God.

What does this have to do with Universalism, past or present? In brief, it is one thing to profess Universalism and its another thing to live it. Living it is far harder, in part because it’s not a matter of making a theological commitment and sticking to it. Life that comes from theological commitments requires continuous evaluation and moral decision making. Our life together challenges any hidden self-centeredness. We present one another with carefully considered models of living. This makes it easier to do the right thing, and not merely say it, and so live a life in harmony with God — even before the final harmony.

After Murray

I suppose it should go without saying that you can be a devout, sincere ember of this church without believing anything John Murray preached. You could have even done that in 1805. And so we announce each Sunday a definition of liberalism as “having no credal test for membership.” At most. Universalists wanted to be known as having a common hope without dwelling in the details of how that might happen or what that might look like. Issues that brought other denominations to their knees barely set a ripple among the Universalists, and when there were controversies, the leadership tended to choose broadness over exclusion. It’s a heritage worth keeping.

Closing

Dearly beloved, we are with this church because pioneers, founders and leaders built something that has continued to this day. But nothing is given, nothing is guaranteed.

Each of us must decide what is valuable and everlasting, and what is partial and ephemeral. What is essential and life-giving, and what is dispensable and secondary. As St. Paul said, “Prove all things; hold fast that which is good.” (1 Thess. 5:21.)

Reputation, legacies, plans and fortunes rise but more easily fall. Commit yourself in word and deed to the good, the God-facing direction that brings life and health.

God bless you this day and evermore.

A Universalist Catechism, part five

So, back in 2004, I set out to type out the 1921 Universalist Catechism, but gave up because I found the theology modernist and dreary. Recently, I read a reference to it, and tried to search for a copy online — only to find my suspended series. (That happens more that I care to admit.) So, I knew I had a copy and have dug it out. Now, I’ll finish the series: my theology has changed in fifteen years, and if not that, at least voice recognition software has improved.

The previous parts of this series:

- A Universalist Catechism, part one

- A Universalist Catechism, part two

- A Universalist Catechism, part three

- A Universalist Catechism, part four

What is God’s will towards all men?

He wills that all should be saved.

Can God’s will be defeated?

No. He is sure to be victorious.

Will God give up His purpose because men do not find the right way to live in this life?

No. His life is the same yesterday, to-day, and forever, in this world and in all worlds.

What becomes of man at death?

His body dies and wastes away. His spirit lives on.

Why is it reasonable that men shall live after their bodies die?

Men are children and heirs of the Heavenly Father.

Do all Christians accept this faith you have described?

Not all.

Why do you accept it?

Because it exceeds agrees with reason, is supported by the Bible, and is the best expression of Christianity that I know.

What is the name given to the church that teaches this faith?

The Universalist Church.

What are its essential principles?

The Universal Fatherhood of God,

The spiritual authority and leadership of His Son Jesus Christ,

The trustworthiness of the Bible as containing a revelation from God,

The certainty of just retribution for sin,

The final harmony of all souls with God.

When were these principles first taught?

These principles are found in the teaching of Jesus Christ. They were explicitly taught by the early Christian Church.

When does Universalism disappear from the teaching of the Church?

In the sixth century, when it was condemned as heresy.

Where was the first organized church of the Universalist faith?

At Gloucester, Mass.

Who was the first minister of this church?

John Murray, who came to America from England in 1770.

Who is called the father of Universalist theology?

Hosea Ballou, because he first stated many of the doctrines of the Universalist Church.

Where is the oldest Universalist church building?

At Oxford, Mass.

In John Murray’s time, upon what was the principal emphasis of Universalist teaching?

Upon the truth that all men will be saved.

Upon what is the chief emphasis to-day?

Upon the Universal Fatherhood of God, implying universal brotherhood among men; and upon the certainty of retribution for sin.

Why has this change taken place?

Because men have come to see the importance of applying faith to life.

What is mean by what is meant by applied Universalism?

The application of the principles of Universalism to the problems of daily life.

Who really believes in the Fatherhood of God?

He who lives as if God were his Father.

Who really believes in the leadership of Jesus?

He who follows Jesus Christ and helps to make his ideals real.

Who really believes in the Bible?

He who uses it as a guide-book to life.

Who really believes in retribution for sin?

He who stop sinning and tries to cure the sins of society.

Who really believes the final triumph of good?

He who works untiringly and unfalteringly for that triumph.

Is it enough to apply Universalism to the life of the individual?

No. It must be applied to every problem of society.

What is the duty of every Universalist?

To understand fully the teaching of his Church, to try to apply that teaching to life and its problems, and to win others to the same faith and conduct.

Examining the Universalist theory of worship

So, what makes Universalist worship Universalist? What keys do we have, if we want to build on a tradition?

It turns out that it’s harder to say than in other denominational traditions, including the Unitarian. The problem may date to the beginning, by which I mean the 1790 Philadelphia Convention, where the assembled delegates claimed, “as we have no rules laid down in the word of God to direct us in our choice of a mode or form of public worship, it is recommended to each Church to use such modes and forms of prayer, and to sing such psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs, as to them shall appear most agreeable to the word of God, or best suited to promote order, and spiritual edification.” Not a sense shared by many of their contemporaries! Whether this was an act of liberality, or a politic act of evasion, I will leave for you to decide.

Universalism was made up of different streams, united by a common hope in a common salvation. Other doctrines were a matter of liberty — one reason theological unitarianism had a place — and so much for liturgy, too. As such, the various hymnals and worship books had denominational sponsorship and could be widely adopted and still be entirely optional.

After the Civil War, institutional Universalism congealed around a common program and denominational governance. The theologial schools and denomintational press were growing in influence, and yet there was little discussion about how this new structure applied to worship. Prayerbooks could go out without a preface; liturgists, like Charles Hall Leonard, could write the works, but scarcely say what they intended.

So, where to look for clues? Private papers? Articles in the weekly papers, as yet little digitized? But it may be as subtle as examining the more popular texts themselves, and see what was used, discern what the source documents were — the Episcopal Church’s Book of Common Prayer and the prayerbooks of James Martineau, surely — and see what they thought to change…

Introductions to Universalism

A nice chat with other member of Universalist National Memorial Church after services today, over coffee. As sometimes happens, the matter of books came up, which merged with another comment about Hosea Ballou, and from there to books about Universalism.

I recommended two smallish, straight-forward books and a documentary history, if with reservations. Both are institutional histories, and both are irenic towards Unitarianism, positing Universalism as a close relation rather than a religious tradition on its own terms. Fine as denominational works, but also a bit unsatisfying for informing a faith, particularly a Christian faith. Of course, theological universalism is hot now — in evangelical circles, and so many of the faith-forward works are better for evangelicals. And the academic works are good for academics.

There’s room for a primer. In the mean time, here are those three books.

- The Larger Faith by Charles A. Howe

- American Universalism by George Huntston Williams

- Universalism in America: A Documentary History of a Liberal Faith, ed. by Ernest Cassara

All three are from Skinner House, but only the first two are available at the UUA Bookstore.

Checking in on the book project

Get used to these check-ins; otherwise, it may be too easy to throw the idea of a book on the scrapheap of good intentions. For one thing, it looks like I may be envisioning not one work, but three.

- A book about what Universalist Christianity, in a liberal vein, might look like today. And not necessarily a majoritarian view. Somewhat practical. Not too long. This would ideally be published by an existing press, and would be what I would pitch first to Skinner House.

- A documentary history. A corrective, in some sense, to what we have. This might be a self-published work or perhaps a website. The readership would be small, but important, but not so important to justify the publishing or promotion costs (or effort) a traditional approach demands.

- A monograph or other shorter subject answering the “so, what did happen to Universalist Christianity?” Perhaps for a journal, and to scratch that itch and to keep the first book in the present, and perhaps not so morose.

A preacher, after all, needs not put everything in one sermon.

The full Hosea Ballou quotation

I’ve seen many, many uses by Unitarian Universalists of a passage from Hosea Ballou since the crisis in Ferguson, Missouri after Michael Brown’s shooting death and Darren Wilson’s investigation. The quotation, sourced from the service element section of the most-commonly used Unitarian Universalist hymnal, Singing the Living Tradition, is edited for worship. Number 705:

If we agree in love, there is no disagreement that can do us any injury,

but if we do not, no other agreement can do us any good.

Let us endeavor to keep the unity of the spirit in the bonds of peace.

I wondered what the original was, and how edited it got, particularly since these hymnal elements get used so much (to the exclusion of other writings) that they take on a quasi-canonical character. Even if the quotation is ersatz. (Someone asked me, “That isn’t really Ballou, is it?”) It is, but only in a limited way.

For one thing, the context of the hymnal version suggests quasi-Pauline

advice to a congregation or group. As if he was putting another way Romans 16:17, “Now I beseech you, brethren, mark them which cause divisions and offences contrary to the doctrine which ye have learned; and avoid them.” But that’s not what Ballou was getting at. Here’s the citation, in context from section 224 (“A plea for unselfishness and love.”) in the last print (1986, from a 1882 original) edition of the Treatise on Atonement,

Should we be tenacious about certain sentiments and peculiarities of faith, the time is not far distant when Universalists, who suffered every kind of contemptuous treatment from enemies of the doctrine, will be at war among themselves, and being trodden under the foot of the Gentiles. Having begun in the Spirit do not think to be made perfect by the flesh. In order to imitate our Saviour, let us, like him, have compassion on the ignorant and those whom we view to be out of the way. Attend to the exhortation, “Let brotherly love continue.” If we agree in brotherly love, there is no disagreement that can do us any injury; but if we do not no other agreement can do us any good. Let us keep a strict guard against the enemy “that sows discord among brethren.” Let us endeavor to “keep the unity of the Spirit in the bonds of peace.” May charity, that heaven born companion of the human heart, never forsake us; and may the promise of the Saviour be fulfilled concerning us, “Lo, I am with you alway, even unto the end of the world.”

An even broader context makes it clear that Ballou is cautioning Universalists to maintain humility lest they fall into hubris and error, and continues with an appeal to non-Universalists to examine their claims with patience. Ballou disavows judgement. All good things but not how it comes across in the hymnal.

Also, the hymnal version bleeds out the Christian character of the passage. I can’t add much to that. I’ll end with citing the biblical passages above:

- “Let brotherly love continue.” Hebrews 13:1.

- “that sows discord among brethren.” Proverbs 6:19.

- “keep the unity of the Spirit in the bonds of peace.” Ephesians 4:3. (“Bond” in King James.)

- “Lo, I am with you alway, even unto the end of the world.” Matthew 28:20.